Earlier this year I received my contributor copy of a new anthology from Grey Hen Press, Two Ravens – Explorations of mind and memory. It’s a substantial and impressive collection exploring its important themes from many different angles, through poems written by older women poets. I’m honoured that my poem The Sheffield Man is included amongst poems by such esteemed poets such as Lorna Goodison, Gillian Clark, Imtiaz Dharker and many others.

As I read my way through the anthology, I made a note of those poems that resonated with me or struck me in some other way – and there were many. But one in particular captured and intrigued me, so much so that I typed it out, printed it and stuck to the back of the toilet door. The poem is soul, water by Katharine Towers, a poet I hadn’t come across before. It’s not a mirror poem, but it does circle back to its beginning at the end. The sea, the soul, water – all these speak to me. And there is both grief and comfort in the poem, which refers to the poet’s mother.

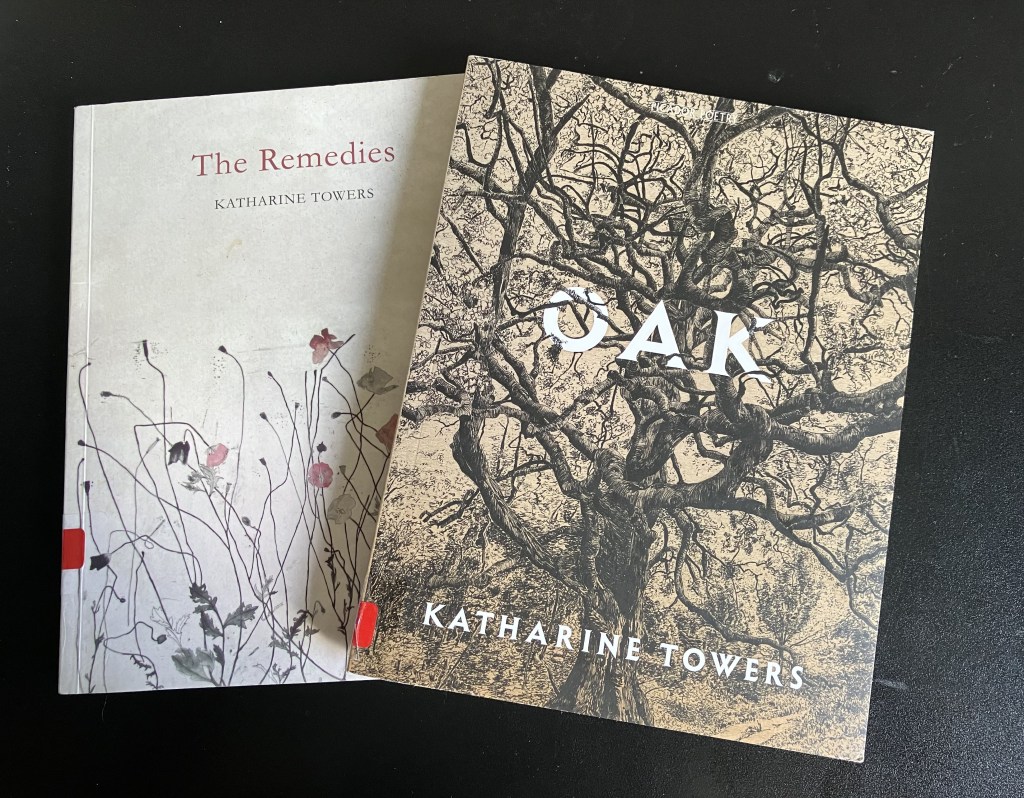

Towers’ biographical note at the back of the anthology mentions she has three collections published by Picador, and a recent pamphlet from The Makers Press ‘exploring the life and music of English composer Gerald Finzi.’ Once I’d finished reading Two Ravens, I headed over to the National Poetry Library to see if they had any of Towers’ collections on the shelves. I came away with The Remedies, published in 2015, and Oak, published in 2021.

I’ve read and reread both volumes, and find her poems intriguing, quietly lyrical, and feeding my atheist soul. Her touch is often light and serious at the same time. The middle section of The Remedies is a sequence of poems based on the plants and flowers used in Bach flower remedies, where the plants are imagined to be afflicted by the issue the remedy is supposed to cure. Nature, particularly the English countryside, features in many of her poems, but there are also a handful of poems in response to other poets and poems, and the difficulties of translation.

Oak charts the long life of an oak tree from the first sprouting of an acorn through to its ‘long vanishment into earth’. The poem’s seven sections create seven arboreal ages that echo the seven ages of man. The sequence is an imaginative tour de force, brimming with exquisite and sometimes humorous detail, revealing more on each rereading.

Next on my to do list is seeking out a copy of Towers’ let him bring a shrubbe, her pamphlet of poems inspired by the composer Gerald Finzi. I’m a fan of Finzi’s music, and now I think about it, sound and music are important elements in Towers’ poetry, so this sounds like a perfect match.